With the start of the new century ASSITEJ-Spain underwent a marked change. The arrival of young professionals into children’s theatre bringing with them innovative ideas and committed to the problems of the society in which they live, along with the development of our young audience, meant an obvious step forward in terms of quality and strictness for theatrical arts geared towards infants and young people.

Interaction between writers, performers and directors has its roots in the decade of the seventies with young people taking to the stage, thus allowing for the handling of topics forbidden during the dictatorial period of censorship with its imposition of rigid criteria. In a series of theatrical encounters held in the city of Granada, professionals working there reached the conclusion that there were no taboo topics for theatre aimed towards the youngest audience, rather that the development of conflicts was not properly handled, along with the lack of new contemporary methods in the majority of the productions.

At the present time plays are performed portraying social problematic issues existing in the world that aim to ease the image with which we are commonly bombarded by the mass media. The staging of numerous works offers theatregoers poetic, innovative and ground-breaking visions of the problems faced by teenagers in our societies.

Dance performances performed by some companies in recent years have placed the youthful audience before new forms of expressive language containing notable levels of quality. We must also make reference to the evident strides forward taken by puppet theatres offered by companies that have evolved not only in terms of technique, but rather also in the artistic and constructive conceptuality of their characters.

Against a backdrop of difficult economic times, severe budget reductions and disproportionate taxation burdens placed on theatrical arts, professionals working in our children’s theatres and the youth have managed to resist and show the true worth of the theatre as part of artistic education. This challenge from the sector has been acknowledged by many parents in an increasingly persistent manner, who attend with their children high quality performances of shows intended for the youngest members of society. (l),

Undoubtedly, there is still much ground to be covered, however, we are confident that in the coming half century the cooperation between all the national centres that comprise the ASSITEJ will embrace our common goals of achieving the necessary interaction and knowledge of new theatrical languages that youngsters are offering in their respective countries.

Luis Matilla

(I) Optional paragraph

The publication by ASSITEJ-Spain of an extensive collection of theatrical texts, in tandem with the work of other publishing houses, has allowed for the general public to be aware of numerous new generation authors, thus facilitating the reading of their works in a wide number of educational centres all over the country.

Inter-Generational Exchange? In the theatre?

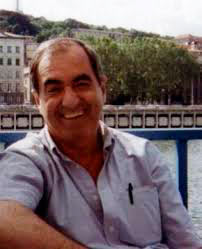

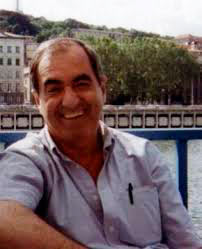

Jesús Campos García

I must say something, I feel the need to get it off my chest, to know who you want to tell and find the way of doing so is the channel that all forms of communication must take. This is also the case for the creative and dramatic arts, as well as children’s theatre. Only on two occasions throughout my writing career have I focused my attentions on a youthful audience, particularly infants. I have always been of the opinion that any work intended for adults can awaken the interest of younger readers, and can attest to this. On one occasion, due to rather bizarre circumstances, a group of students, with their teacher at the lead, came to see the least “childish” of my works “It is a lie”, a nightmare in which a group of giant rats gun down the main character at the end. The attention with which these children attended the performance (they were terrified) dismantles any argument with which one would aim to defend the need for a separate theatre for children. And why not flip the terms of the pretext: why can works intended for children not be equally interesting for an adult audience?

Between 76 and 78 (the so-called Transition from dictatorship to democracy) there was a lot to be said and I felt the need to say it. And as, at the same time, there was the coincidence that my children were still infants, I tried to put this into context for them with the strategies I considered most appropriate. We are not dwarves, we are giants – and this was something that we need to bear in mind if we did not want to be manipulated. The Stepmother, the Queen, in short, the powers that be wanted the dwarves to work in a diamond mine in order to augment their own beauty, or wealth, instead of allowing them to mine coal with which they could keep warm. The innocence of Snow White or the arrival of the Dashing Prince was told in a different way that would mark the transition from the traditional version to the new Snow White and the 7 Giants, in which resistance and struggle against the interior enemy was brought to the stage.

Many years passed, and also a lot of life, so that other stories needed telling, other that I felt the need to tell. Drugs, something which had happened to me right on my doorstep, was the issue with which I once again geared my work towards a younger audience, on this occasion my grandchildren with Saint George and the Dragon, the popular legend that I used as a backdrop to create the tale. The city under siege by the dragon that lives in its sewers hands over its youth as a form of taxation, thus trying to maintain a balance between the pestilence and economic perks that such business creates. Saint George is then required to come to their aid, though he says that he is rather busy killing his own dragons and that they should act without waiting for anyone to come and save them, as we all must make efforts to defend our own city. Finally, when the main character dies, his friends await, as can only happen in stories, a miracle to happen and a happy ending, when they will finally understand, much to their dismay, that this will not happen because drugs are no fairy-tale.

There was never to be a third occasion, although at times I have tried; yet, I never had a clear idea or never knew who to address the work to. Writing organically brings with it problems. To say, therefore, that with my work I have been able to contribute to international dialogue would seem somewhat over-the-top. Even if I had written hundreds of plays for children, I would not make this claim.

Theatre written by adults for children or the youth establishes a means of communication, but not dialogue. Dialogue requires a reciprocal nature – that we as adults must also be receptors of the dramatisations with which they express their emotions. A number of years ago a group of authours belonging to the AAT (Theatrical Writers’ Association) visited secondary schools to encourage students to put their theatrical writing ability to the test, as they naturally day with narrative texts. When we are all broadcasters and receptors, then there can be dialogue. An unequal dialogue, yet not in vain.

In the 70s, a girl, not more than fourteen years old, cared for my children, who were at the time between five and nine, when they went to the beach. She did this in the summer, but it turned out that in the winter she did the same, as we would later see that she worked in other houses doing other “occupations”. The girl, whose name escapes me unfortunately, when she discovered I was a playwright, felt the need to do the same and, without writing it down, made up a scene that she had memorised with my daughter. The girl was the maid and my daughter the lady of the house. It still amazes me to remember how she did not get side-tracked with tales and fantasy, but rather stuck to the story in its most real form. The maid, with her broom in hand, swept nervously and fearfully as she awaited the arrival of the lady of the house, as, according to her words, everything was still to be done. And indeed, when the lady of the house arrived, she began to shout at the maid for leaving the place to rack and ruin. Attending that crude performance was the closest I have ever been to an inter-generational dialogue. The work ended with the maid’s mutiny, throwing the broom to the floor and exiting shouting “F**k the broom and the boss”.

Playwright, National Award for Dramatic Literature, president of the AAT (Theatrical Writers’ Association, with whom Assitej Spain carries out projects together). The majority of his lauded work is written for adults, though he has made two incursions into the world of children’s theatre with, Snow White and the 8 Giants and the Corrupt Beast.

With the start of the new century ASSITEJ-Spain underwent a marked change. The arrival of young professionals into children’s theatre bringing with them innovative ideas and committed to the problems of the society in which they live, along with the development of our young audience, meant an obvious step forward in terms of quality and strictness for theatrical arts geared towards infants and young people.

Interaction between writers, performers and directors has its roots in the decade of the seventies with young people taking to the stage, thus allowing for the handling of topics forbidden during the dictatorial period of censorship with its imposition of rigid criteria. In a series of theatrical encounters held in the city of Granada, professionals working there reached the conclusion that there were no taboo topics for theatre aimed towards the youngest audience, rather that the development of conflicts was not properly handled, along with the lack of new contemporary methods in the majority of the productions.

At the present time plays are performed portraying social problematic issues existing in the world that aim to ease the image with which we are commonly bombarded by the mass media. The staging of numerous works offers theatregoers poetic, innovative and ground-breaking visions of the problems faced by teenagers in our societies.

Dance performances performed by some companies in recent years have placed the youthful audience before new forms of expressive language containing notable levels of quality. We must also make reference to the evident strides forward taken by puppet theatres offered by companies that have evolved not only in terms of technique, but rather also in the artistic and constructive conceptuality of their characters.

Against a backdrop of difficult economic times, severe budget reductions and disproportionate taxation burdens placed on theatrical arts, professionals working in our children’s theatres and the youth have managed to resist and show the true worth of the theatre as part of artistic education. This challenge from the sector has been acknowledged by many parents in an increasingly persistent manner, who attend with their children high quality performances of shows intended for the youngest members of society. (l),

Undoubtedly, there is still much ground to be covered, however, we are confident that in the coming half century the cooperation between all the national centres that comprise the ASSITEJ will embrace our common goals of achieving the necessary interaction and knowledge of new theatrical languages that youngsters are offering in their respective countries.

Luis Matilla

(I) Optional paragraph

The publication by ASSITEJ-Spain of an extensive collection of theatrical texts, in tandem with the work of other publishing houses, has allowed for the general public to be aware of numerous new generation authors, thus facilitating the reading of their works in a wide number of educational centres all over the country.

Inter-Generational Exchange? In the theatre?

Jesús Campos García

I must say something, I feel the need to get it off my chest, to know who you want to tell and find the way of doing so is the channel that all forms of communication must take. This is also the case for the creative and dramatic arts, as well as children’s theatre. Only on two occasions throughout my writing career have I focused my attentions on a youthful audience, particularly infants. I have always been of the opinion that any work intended for adults can awaken the interest of younger readers, and can attest to this. On one occasion, due to rather bizarre circumstances, a group of students, with their teacher at the lead, came to see the least “childish” of my works “It is a lie”, a nightmare in which a group of giant rats gun down the main character at the end. The attention with which these children attended the performance (they were terrified) dismantles any argument with which one would aim to defend the need for a separate theatre for children. And why not flip the terms of the pretext: why can works intended for children not be equally interesting for an adult audience?

Between 76 and 78 (the so-called Transition from dictatorship to democracy) there was a lot to be said and I felt the need to say it. And as, at the same time, there was the coincidence that my children were still infants, I tried to put this into context for them with the strategies I considered most appropriate. We are not dwarves, we are giants – and this was something that we need to bear in mind if we did not want to be manipulated. The Stepmother, the Queen, in short, the powers that be wanted the dwarves to work in a diamond mine in order to augment their own beauty, or wealth, instead of allowing them to mine coal with which they could keep warm. The innocence of Snow White or the arrival of the Dashing Prince was told in a different way that would mark the transition from the traditional version to the new Snow White and the 7 Giants, in which resistance and struggle against the interior enemy was brought to the stage.

Many years passed, and also a lot of life, so that other stories needed telling, other that I felt the need to tell. Drugs, something which had happened to me right on my doorstep, was the issue with which I once again geared my work towards a younger audience, on this occasion my grandchildren with Saint George and the Dragon, the popular legend that I used as a backdrop to create the tale. The city under siege by the dragon that lives in its sewers hands over its youth as a form of taxation, thus trying to maintain a balance between the pestilence and economic perks that such business creates. Saint George is then required to come to their aid, though he says that he is rather busy killing his own dragons and that they should act without waiting for anyone to come and save them, as we all must make efforts to defend our own city. Finally, when the main character dies, his friends await, as can only happen in stories, a miracle to happen and a happy ending, when they will finally understand, much to their dismay, that this will not happen because drugs are no fairy-tale.

There was never to be a third occasion, although at times I have tried; yet, I never had a clear idea or never knew who to address the work to. Writing organically brings with it problems. To say, therefore, that with my work I have been able to contribute to international dialogue would seem somewhat over-the-top. Even if I had written hundreds of plays for children, I would not make this claim.

Theatre written by adults for children or the youth establishes a means of communication, but not dialogue. Dialogue requires a reciprocal nature – that we as adults must also be receptors of the dramatisations with which they express their emotions. A number of years ago a group of authours belonging to the AAT (Theatrical Writers’ Association) visited secondary schools to encourage students to put their theatrical writing ability to the test, as they naturally day with narrative texts. When we are all broadcasters and receptors, then there can be dialogue. An unequal dialogue, yet not in vain.

In the 70s, a girl, not more than fourteen years old, cared for my children, who were at the time between five and nine, when they went to the beach. She did this in the summer, but it turned out that in the winter she did the same, as we would later see that she worked in other houses doing other “occupations”. The girl, whose name escapes me unfortunately, when she discovered I was a playwright, felt the need to do the same and, without writing it down, made up a scene that she had memorised with my daughter. The girl was the maid and my daughter the lady of the house. It still amazes me to remember how she did not get side-tracked with tales and fantasy, but rather stuck to the story in its most real form. The maid, with her broom in hand, swept nervously and fearfully as she awaited the arrival of the lady of the house, as, according to her words, everything was still to be done. And indeed, when the lady of the house arrived, she began to shout at the maid for leaving the place to rack and ruin. Attending that crude performance was the closest I have ever been to an inter-generational dialogue. The work ended with the maid’s mutiny, throwing the broom to the floor and exiting shouting “F**k the broom and the boss”.

Playwright, National Award for Dramatic Literature, president of the AAT (Theatrical Writers’ Association, with whom Assitej Spain carries out projects together). The majority of his lauded work is written for adults, though he has made two incursions into the world of children’s theatre with, Snow White and the 8 Giants and the Corrupt Beast.

With the start of the new century ASSITEJ-Spain underwent a marked change. The arrival of young professionals into children’s theatre bringing with them innovative ideas and committed to the problems of the society in which they live, along with the development of our young audience, meant an obvious step forward in terms of quality and strictness for theatrical arts geared towards infants and young people.

Interaction between writers, performers and directors has its roots in the decade of the seventies with young people taking to the stage, thus allowing for the handling of topics forbidden during the dictatorial period of censorship with its imposition of rigid criteria. In a series of theatrical encounters held in the city of Granada, professionals working there reached the conclusion that there were no taboo topics for theatre aimed towards the youngest audience, rather that the development of conflicts was not properly handled, along with the lack of new contemporary methods in the majority of the productions.

At the present time plays are performed portraying social problematic issues existing in the world that aim to ease the image with which we are commonly bombarded by the mass media. The staging of numerous works offers theatregoers poetic, innovative and ground-breaking visions of the problems faced by teenagers in our societies.

Dance performances performed by some companies in recent years have placed the youthful audience before new forms of expressive language containing notable levels of quality. We must also make reference to the evident strides forward taken by puppet theatres offered by companies that have evolved not only in terms of technique, but rather also in the artistic and constructive conceptuality of their characters.

Against a backdrop of difficult economic times, severe budget reductions and disproportionate taxation burdens placed on theatrical arts, professionals working in our children’s theatres and the youth have managed to resist and show the true worth of the theatre as part of artistic education. This challenge from the sector has been acknowledged by many parents in an increasingly persistent manner, who attend with their children high quality performances of shows intended for the youngest members of society. (l),

Undoubtedly, there is still much ground to be covered, however, we are confident that in the coming half century the cooperation between all the national centres that comprise the ASSITEJ will embrace our common goals of achieving the necessary interaction and knowledge of new theatrical languages that youngsters are offering in their respective countries.

Luis Matilla

(I) Optional paragraph

The publication by ASSITEJ-Spain of an extensive collection of theatrical texts, in tandem with the work of other publishing houses, has allowed for the general public to be aware of numerous new generation authors, thus facilitating the reading of their works in a wide number of educational centres all over the country.

Inter-Generational Exchange? In the theatre?

Jesús Campos García

I must say something, I feel the need to get it off my chest, to know who you want to tell and find the way of doing so is the channel that all forms of communication must take. This is also the case for the creative and dramatic arts, as well as children’s theatre. Only on two occasions throughout my writing career have I focused my attentions on a youthful audience, particularly infants. I have always been of the opinion that any work intended for adults can awaken the interest of younger readers, and can attest to this. On one occasion, due to rather bizarre circumstances, a group of students, with their teacher at the lead, came to see the least “childish” of my works “It is a lie”, a nightmare in which a group of giant rats gun down the main character at the end. The attention with which these children attended the performance (they were terrified) dismantles any argument with which one would aim to defend the need for a separate theatre for children. And why not flip the terms of the pretext: why can works intended for children not be equally interesting for an adult audience?

Between 76 and 78 (the so-called Transition from dictatorship to democracy) there was a lot to be said and I felt the need to say it. And as, at the same time, there was the coincidence that my children were still infants, I tried to put this into context for them with the strategies I considered most appropriate. We are not dwarves, we are giants – and this was something that we need to bear in mind if we did not want to be manipulated. The Stepmother, the Queen, in short, the powers that be wanted the dwarves to work in a diamond mine in order to augment their own beauty, or wealth, instead of allowing them to mine coal with which they could keep warm. The innocence of Snow White or the arrival of the Dashing Prince was told in a different way that would mark the transition from the traditional version to the new Snow White and the 7 Giants, in which resistance and struggle against the interior enemy was brought to the stage.

Many years passed, and also a lot of life, so that other stories needed telling, other that I felt the need to tell. Drugs, something which had happened to me right on my doorstep, was the issue with which I once again geared my work towards a younger audience, on this occasion my grandchildren with Saint George and the Dragon, the popular legend that I used as a backdrop to create the tale. The city under siege by the dragon that lives in its sewers hands over its youth as a form of taxation, thus trying to maintain a balance between the pestilence and economic perks that such business creates. Saint George is then required to come to their aid, though he says that he is rather busy killing his own dragons and that they should act without waiting for anyone to come and save them, as we all must make efforts to defend our own city. Finally, when the main character dies, his friends await, as can only happen in stories, a miracle to happen and a happy ending, when they will finally understand, much to their dismay, that this will not happen because drugs are no fairy-tale.

There was never to be a third occasion, although at times I have tried; yet, I never had a clear idea or never knew who to address the work to. Writing organically brings with it problems. To say, therefore, that with my work I have been able to contribute to international dialogue would seem somewhat over-the-top. Even if I had written hundreds of plays for children, I would not make this claim.

Theatre written by adults for children or the youth establishes a means of communication, but not dialogue. Dialogue requires a reciprocal nature – that we as adults must also be receptors of the dramatisations with which they express their emotions. A number of years ago a group of authours belonging to the AAT (Theatrical Writers’ Association) visited secondary schools to encourage students to put their theatrical writing ability to the test, as they naturally day with narrative texts. When we are all broadcasters and receptors, then there can be dialogue. An unequal dialogue, yet not in vain.

In the 70s, a girl, not more than fourteen years old, cared for my children, who were at the time between five and nine, when they went to the beach. She did this in the summer, but it turned out that in the winter she did the same, as we would later see that she worked in other houses doing other “occupations”. The girl, whose name escapes me unfortunately, when she discovered I was a playwright, felt the need to do the same and, without writing it down, made up a scene that she had memorised with my daughter. The girl was the maid and my daughter the lady of the house. It still amazes me to remember how she did not get side-tracked with tales and fantasy, but rather stuck to the story in its most real form. The maid, with her broom in hand, swept nervously and fearfully as she awaited the arrival of the lady of the house, as, according to her words, everything was still to be done. And indeed, when the lady of the house arrived, she began to shout at the maid for leaving the place to rack and ruin. Attending that crude performance was the closest I have ever been to an inter-generational dialogue. The work ended with the maid’s mutiny, throwing the broom to the floor and exiting shouting “F**k the broom and the boss”.

Playwright, National Award for Dramatic Literature, president of the AAT (Theatrical Writers’ Association, with whom Assitej Spain carries out projects together). The majority of his lauded work is written for adults, though he has made two incursions into the world of children’s theatre with, Snow White and the 8 Giants and the Corrupt Beast.

Cartas

The 22nd ASSITEJ Korea International Summer Festival was evaluated as “very excellent” grade by the Arts Council Korea.

The evaluation was made for all programs of arts and culture financially supported by the Arts Council Korea last year. The 22nd ASSITEJ Korea International Summer Festival in 2014 was rated top as the one and only performing arts festival, and chosen as 1 of the 3 most excellent arts and cultural activities in Korea.

The evaluation was made in the categories of 5 areas, and the Festival was highly ranked, over 90%, especially in artistic contribution, programming, and management of festival organization.

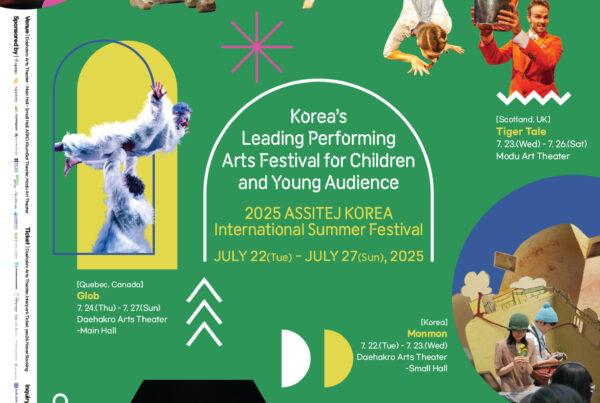

9 Korean and 1 international quality theatre pieces for children will be presented in 14 local towns

“Art Dream Theatre Festival for Local Young Audiences 2015” marks its 6th edition after more than 40 times in 14 local towns, the biggest in terms of geographical scale since its establishment.

“Art Dream Theatre Festival for Local Young Audiences 2015” marks its 6th edition after more than 40 times in 14 local towns, the biggest in terms of geographical scale since its establishment.

Unlike 2 other festivals organized by ASSITEJ Korea, this Festival does not take place in Seoul, but in local cities and small towns where cultural activities are rare and children are culturally isolated. Moreover, for the first time, the international piece will be presented to local young audiences and their parents, and “Overture” by Teatergruppen Batida from Denmark was chosen to be presented at 3 venues.

14 towns, 9 across the Korean Peninsula, are new to the program of the Festival. Supported by Hyundai Motor Group, a world-renowned motor company in Korea, the Festival will begin on October 5 and continue till October 28, 2015.

Over the past 5 years, approximately 12,000 local audiences were benefitted by this arts and culture program.

Secretary General of ASSITEJ, Ms. Marisa Giménez Cacho, invited to ASSIETJ Korea

Ms. Marisa Giménez Cacho, Secretary General of ASSITEJ, will meet Korean professionals of TYA and enjoy the 23rd ASSITEJ Korea International Summer Festival.

During her stay in Seoul from July 19 to 25, 2015, she is planning to have a round table discussion with members of ASSITEJ Korea in order to introduce TYA in Mexico and share her experiences in international networking as one of the key members of ASSITEJ.

Exchange programs between ASSITEJ Korea and Mexico with Dr. KIM Sookhee, the president of ASSITEJ Korea, within the framework of celebration project of diplomatic relations between the 2 counties in 2017 will also be discussed.